Bronze Age Weapons

New

technologies to refine, smelt and cast metal ores

were first used during the Bronze Age

(c.3500—700BC). Early civilizations in the Middle

East began to combine bronze or copper alloys to

produce spears, daggers, swords and axes. Later, swordsmiths started producing finely detailed swords

with stronger iron blades. These techniques spread

to China, India, South-east Asia and Europe, where

they would have a profound influence on future

warfare.

This short sword was made between 3200 and 1150BC.

The decorated hilt and round pommel were later

replacements.

Early Metal Weapons

With the

introduction of copper alloys (90 percent copper

and 10 percent tin), the bronzesmith was able to

produce a much harder metal. Its hardness and

consequent durability were wholly dependent on the

temperature that could be achieved during smelting.

The higher the temperature, the harder the metal

would become. Iron ore was also discovered and soon

became the material of choice for the production of

bladed weapons. Iron ore was abundant and, like

copper alloys, it could be heated to high

temperatures by using charcoal. Immersion of the

blade in water and continuous hammering to form a

well-tempered blade developed a consistent surface

that was less prone to fracture and breakage than

bronze or copper. Most blades would have been cast

in stone, metal or clay moulds.

The sword in Europe from c.2000BC

Although it is

difficult to date precisely when the sword was first

introduced into Europe, there is general agreement

that long-bladed swords were being manufactured

around 2000BC. Their appearance in Europe was

probably independent of earlier developments in

metalworking seen in the Near East and the Aegean.

Distinctive flint swords have been found from this

date in Denmark and northern Europe, including

riveted bronze swords with triangular blades from

the early Bronze Age.

In the later Bronze Age, swords

were cast in one piece, including the grip and

pommel (the knob at the top of the handle or hilt).

Many differing pommel

shapes also emerged. One of the most common swords

is the antenna (or voluted) sword. This had a two-

pronged or scrolled, inwardly curving pommel, said

to represent the outstretched hands of a human

figure. Sword shapes also varied, from broad-leaf

shapes to straight forms that featured grooves,

sometimes erroneously described as “blood channels”,

but more likely to have been designed to provide a

lighter and more easily wielded sword.

The Carp’s Tongue Sword

Common in western and

eastern Europe around 1000BC were a group of bronze

swords known as “carp’s tongue” swords. A

significant number of this distinct sword type were

discovered at excavations in the Thames Valley and

Kent during the mid-20th century. The most notable

find was at the Isleham Hoard, in Cambridgeshire,

England. It comprised more than 6,500 objects made

of bronze, including many swords of carp’s tongue

design. They had wide, tapering blades which were

useful for slashing, with a thinner, elongated end

suitable for stabbing. This style of sword is

thought to have originated in northwestern France.

The Socketed Axe

Another important

military innovation of the Bronze Age Mesopotamian

armies in the Middle East, and one that would have

an enormous impact on future

battlefield warfare, was the introduction of the

socketed axe. Previously, ancient axe makers had

struggled to keep the axehead firmly attached to the

haft (the handle), especially when handling the axe

with considerable force. The Sumerians devised a

cast bronze socket that slipped over the haft and

was secured with rivets. Its development was

probably a consequence of the introduction of

primitive forms of body armour and the need to

penetrate this armour with sufficient force. Later

axes would have narrower points that could be used

to penetrate bronze plate armour. The axe would

remain an integral battle weapon for the next 2,000

years.

A

complete Bronze Age sword (top) with hilt and

leaf-shaped blade (c.1100BC),

and a large bronze spearhead (bottom) from 700BC.

These Bronze Age socketed axes were used as both

domestic tools and

close-quarter combat weapons.

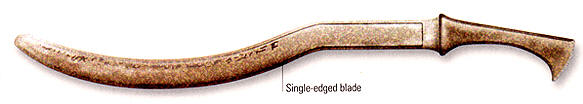

The Sickle Sword of Mesopotamia

One of the earliest societies in which organized

warfare was waged was the Sumerian culture of

southern Mesopotamia (c.3000BC). Even at this early

stage of human civilization, professional standing

armies were being used to defend communities.

Although the most common weapons used by the

Sumerians, and later the Assyrians (c.1100—600BC),

included the spear and bow, warriors also carried a

sharply curved sickle sword.

Introduced around 2500BC, this all-metal sword had a

single-handed grip and a blade of around three grip

lengths. A stunning example in the British Museum,

London, England, has the following inscription on

the blade:

Palace of Adad-nirar, king of the universe, son of Arik-den-ili,

king of Assyria, son of Enlil-nirari, king of

Assyria.

It is believed that this sword was owned by the

Assyrian king Adad-nirari I, who conquered northern

Mesopotamia

(c.1307—1275BC). Mesopotamian art frequently depicts

the sickle sword as a symbol of authority, and it is

often seen placed in the hands of gods and kings.

An illustration of a

sickle sword, 1307—1275BC,

from the Middle Assyrian period (the reign of

Adad-nirari I). |